Back to the front -- 55 years later

The G.I.ís who fought

there named it Sad Sack, but if this tiny hamlet were big enough to appear  on a map of Belgium, it would be called Sadzot. 55 years ago, it was a

battleground for Hitlerís final offensive parry in the Battle of the Bulge,

a last ditch effort to recover momentum lost at Bastogne and seize a key

road which would open the way to get his forces north to Antwerp. A few

hundred American soldiers were all that stood in the way of crack SS Panzer

units. My father, 19 year-old Howard Werner, was one of them.

on a map of Belgium, it would be called Sadzot. 55 years ago, it was a

battleground for Hitlerís final offensive parry in the Battle of the Bulge,

a last ditch effort to recover momentum lost at Bastogne and seize a key

road which would open the way to get his forces north to Antwerp. A few

hundred American soldiers were all that stood in the way of crack SS Panzer

units. My father, 19 year-old Howard Werner, was one of them.

Earlier this month, he went back to Sadzot for the

first time since that bitterly cold winter of 1944.

My family learned of Howardís role in this place

a few years ago, when we all read a book entitled "Bloody Clash at Sadzot."

Ever since, my wife Liz and I had been pestering him to return for a visit.

He would just wave his hand away and shrug off the

idea. "Thereís nothing there to see, itís just a few houses on a road,"

he would say. While his description would prove technically accurate, it

turned out there was more to see and even more to feel than any of us could

have imagined.

After a fair amount of pestering and cajoling ("Címon

Dad, think of it as one last trip to the front."), Howard agreed to see

Sadzot as part of a trip to Paris on which my siblings and our spouses

accompanied my parents to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary. Sadzot

is about a four-hour drive.

Some of my other family members were even harder

to sell on the trip than my father, so the family excursion force consisted

of my parents, my brother Eric, Liz and me.

In finding out about Sadzot, I had exchanged some

e-mail with a couple of men who had served in the same battalion with my

father. They, in turn, put me in contact with a Dutchman named Ron Van

Rijt, a self-taught expert in Battle of the Bulge history and geography,

who now guides both American and German veterans through their old battlefields.

We arranged to meet Ron in Erezee, the small village

of which Sadzot is a part. Erezee isnít on most maps either, except those

in the books about World War II. Ron wrote me we would have no trouble

finding him since he would be riding down from Holland on a "screaming

yellow motorcycle with sidecar" and, "Erezee has only one main road."

We had hired a driver and van in Paris. Our driver,

Ricardo, turned out to be a Chilean who didnít speak English. He also had

some trouble locating Belgium, much less Erezee. Fortunately, Eric

is pretty good with maps and we managed in our halting Spanish, plus a

few stops for directions, to get Ricardo on the right roads.

When we left Paris that morning, the sky was blue

and the air was crisp. As we drove up into the Ardennes Forest, the weather

turned gray and a cold mist enveloped the day. Peering into the forest

from the van, we saw how dark it was among the trees. Eric and I tried

to picture how it must have been for the soldiers who fought in and among

those woods.

We arrived in Erezee about an hour late, and to

our relief we saw the yellow motorcycle parked on the roadside. We met

Ron, who I would guess to be around 40. He looked like you might expect

a man to look after taking a 60 mile motorcycle trek through a cold November

rain. He had dressed warmly.

We were all hungry and found a little place for

lunch. In spite of the language difficulties ( none of us speak French

-- Ron speaks Dutch, German and English), we managed to get a meal.

Ron told us about his father, who had been taken by the SS during the war

and forced to work in a coal mine and frequently tortured. He also brought

a picture of an American military cemetery in Holland, and proudly explained

it is the only such burial ground in Europe where individual graves are

"adopted" by the townspeople who tend and care for the plots.

"Schoolchildren are brought through this place all

the time," he said, "and are taught who these people are and that they

died in the liberation of our country."

After lunch, we climbed back into the van to drive

to Sadzot. Even though it was only about a mile away, we would never have

found it without Ron to show us where it was. It took about two minutes

to get there, and it probably takes less than that to drive through the

whole place.

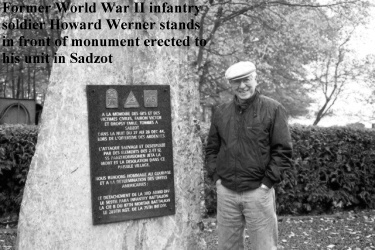

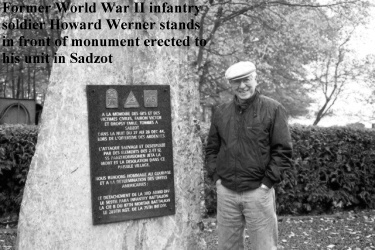

We parked the van, zipped up our coats and walked

over to a monument erected about ten years by the locals ago to honor the

American soldiers who defended Sadzot. Then we walked toward the dozen

or so stone farmhouses which comprise the village. As my father talked,

more details from the story we thought he had already told us began to

emerge.

"I remember one guy," he said, " just came up to

the front and took out a German tank with his first shot from a bazooka.

It was right over there."

All the houses sit on the left side of a road which

might just be wide enough to accommodate two cars. Across the road, the

terrain slopes upward for a few hundred yards among apple trees and a couple

of barns and then it is nothing but trees ĖĖ The Ardennes.

Somewhere up in those woods at midnight on December

27, 1944, in sub-zero temperatures, units of the 2nd and 12th SS Panzer

divisions, elite German troops with four or five years of combat experience,

began to move north for the assault on Sadzot. They emerged from the forest

about 2 a.m.

Corporal Bill Cummings of the 87th Chemical Mortar

Battalion (Company B ĖĖ my fatherís unit) had taken over guard duty at

the same time the Germans had set out. Cummings was big, strapping young

man with a cheerful disposition who was well-liked by his fellow soldiers.

As a child, Cummings had suffered a broken arm which never healed properly

and left him with a permanent crook to his arm. Other soldiers would often

suggest he put in for something less rigorous than combat, but Cummings

would just shrug and smile and go on about his duties.

Unknown to Cummings, Germans had crept up to the

two houses nearest the assault point and slashed the throats of the American

soldiers sleeping there. When Cummings saw the attack force advancing,

they were almost on top of him. He took off to warn the platoons who were

sleeping in the houses along the road.

"Get up, thereís Krauts all over the place," he

shouted. As Cummings ran from house to house, he was hit by German machine

gun fire. He fell dead in the snow.

Inside the house where Cummings had delivered his

last warning, my father had been sleeping with other members of his platoon.

During the Battle of the Bulge, a lot of replacements had been hurriedly

shipped up to the front. Unlike my father who had seen a fair amount of

combat by this time, the new guys didnít know enough to sleep with their

boots on and their rifles within reach. This inexperience would cost a

lot of young men their lives.

My father and his platoon-mates began firing at

the oncoming Germans from the house. A German grenade came flying through

the front door right next to the window out of which my father had been

shooting. He yelled "Grenade!" and ran through a door to the back room,

shutting it behind him just as the explosion rocked the building. Not knowing

who or what was behind the house, the half-dozen or so Americans jumped

out the back window just as the SS troops burst in the front door spraying

machine-pistol fire.

Meanwhile, a lieutenant in the outfit named Gordon

Byers had spotted a nearby American tank with a top-mounted machine gun.

Byers ran over and ordered its commander to move forward. He refused. Byers

took out his .45, placed it to the head of the tank driver and repeated

the order. He moved. Byers led the tank into the fray firing the machine

gun until it was out of ammunition.

My father made it down the road to where the 509th

Parachute Infantry Battalion was positioned. When the 509th saw figures

in the night rushing toward them, they assumed it was Germans and began

to fire machine guns. At least one American was killed this way, until

they were finally able to yell loudly enough above the din to identify

themselves.

The 509th counter-attacked and in my fatherís words,

"went back up there and wiped the floor with Germans." The Americans then

mopped up whatever German forces remained in the surrounding area. When

the fighting in and around Sadzot was all over, some 250 SS troopers lay

dead. The 509th had 120 men killed or wounded.

Of the 70 men in my fatherís company, 53 were either

killed, wounded or captured in the battle for Sadzot. Company B of the

87th Chemical Mortar Battalion was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation

for its actions there.

The whole thing began and ended in less than three

days.

During the fighting, two Sadzot residents and their

nine month-old daughter fled to a basement for shelter. The baby was struck

by a stray bullet. When the village was secured again by American forces,

she was rushed to an aid station for medical treatment. Today, that baby

is the English teacher in the village of Erezee.

Aside from the memorial and some bullet holes in

the farmhouse walls, there is little physical evidence today of what took

place 55 years ago. But, perhaps unlike Americans, Belgians have long national

memories.

As we walked through Sadzot, we stopped to talk

to a woman who lived in the first house we came to. She certainly wasnít

old enough to have been born when her home was a tactical piece of ground

in a pitched battle. And though she didnít speak much English, she and

my father somehow managed to communicate what his visit was all about.

She went into her house and brought out what we think was a French translation

of "Bloody Clash at Sadzot." She and my father looked at the photographs

together and somehow language didnít matter much.

The next house turned out to be the house my father

had been sleeping in that night. It has been re-built and expanded and

is now a weekend home for a married couple who are both doctors in Brussels,

Bernard and Nicole. They are also of post-war vintage. Fortunately for

us, they both speak English. They had their own copy of "Bloody Clash"

(English version) and seemed genuinely thrilled at the opportunity to talk

with my father about his experiences.

They invited us into their home and my father walked

around. He stood by the window where he had fought for his country and

his life, and pointed out that the front door to the house was once six

feet to the right of where it is now. Howard isníít the kind of guy to

get all weepy and blubbery on returning to the scene of so much carnage.

He stood at that window and said. "Yeah, I got a bunch of them right out

there."

Bernard and Nicole then invited us into their family

room. They sat with my father leafing through the photograph sections of

"Bloody Clash." They pointed out the old pictures of their house, while

my father showed them the photo of himself as a young infantryman.

Our hosts brought out shot glasses and a bottle

of a liqueur they explained was made locally.

"We need to toast the occasion," they said. We knocked

back our drinks and while the stuff was delicious, it sure had a bite to

it. Seeing that our eyes were watering, Nicole said sheepishly, "Well you

know the winters here are hard.."

We walked back outside the house, and I couldnít

help but notice the German-made Mercedes Benz parked in front. Irony? Probably

not. Just a reminder that a lot of time has passed, and the world is an

ever-changing place.

We bid Bernard and Nicole goodbye, dropped off Ron

at his motorcycle, and began our return trip to Paris. We stopped briefly

in the next town of Grandmenil to look at a Panzer tank which still sits

by the side of the road to remind people of what took place in the area.

In conversation on the way home, my father corrected

us whenever we referred to the action at Sadzot as a "battle." "It wasnít

a battle," he insisted, "Bastogne ĖĖ that was a battle." I suppose he meant

that battles are fought on a larger scale, with thousands of men involved.

He might be correct in military parlance, but the exchange highlights the

understatement of that singular generation who fought to save the world.

It is telling of their achievement that today we have the liberty to use

"battle" to describe an election or a football game.

Ricardo managed to get us lost again -- he seemed

to think there was a shortcut around Luxembourg, but it didníít bother

us a bit. It would have taken a lot more than a circuitous route to Paris

to put a damper on this day.

When we got back home, the following e-mail was waiting for my

brother:

Dear Mr. Werner,

It was great to meet you and your family in Sadzot

on last Sunday. Surprise was big for us, and time so short... We regret

we did not jump at the opportunity to thank warmly your father for his

so generous courage. He exposed his life for our freedom! We are

grateful and wish very truly the best for him and all his family.

May God protect all of you !

Nicole and Bernard

Every American soldier, or his next of kin, should receive

a letter like that.

I know Iím one of the lucky ones. My father survived

World War II. I had the chance to go back with him and learn some of his

war story. My family and I can to take into the future the remembrance

of this time when the past and present came together. And we have the freedom

to enjoy it.

Thanks, Dad.

-end-

November 18, 1999

on a map of Belgium, it would be called Sadzot. 55 years ago, it was a

battleground for Hitlerís final offensive parry in the Battle of the Bulge,

a last ditch effort to recover momentum lost at Bastogne and seize a key

road which would open the way to get his forces north to Antwerp. A few

hundred American soldiers were all that stood in the way of crack SS Panzer

units. My father, 19 year-old Howard Werner, was one of them.

on a map of Belgium, it would be called Sadzot. 55 years ago, it was a

battleground for Hitlerís final offensive parry in the Battle of the Bulge,

a last ditch effort to recover momentum lost at Bastogne and seize a key

road which would open the way to get his forces north to Antwerp. A few

hundred American soldiers were all that stood in the way of crack SS Panzer

units. My father, 19 year-old Howard Werner, was one of them.